Watch the YouTube version of this post!

It’s available here:

Subscribe to my YouTube channel to access ALL my videos!

In part 6 of my series on Cognitive Therapy, let’s meet Matt.

Matt’s running late for work.

But then he gets stuck behind a school bus making multiple stops. Matt thinks, “Great. This is all I need this morning.”

Then he hits a construction zone. And Matt thinks, “This is getting ridiculous.”

When he finally reaches the street where his office is located, he hits every single red light.

Matt is ready to explode. He yells, “I can’t believe this awful day! I can’t stand it!”

Have you ever had a morning like this? It’s frustrating, right?

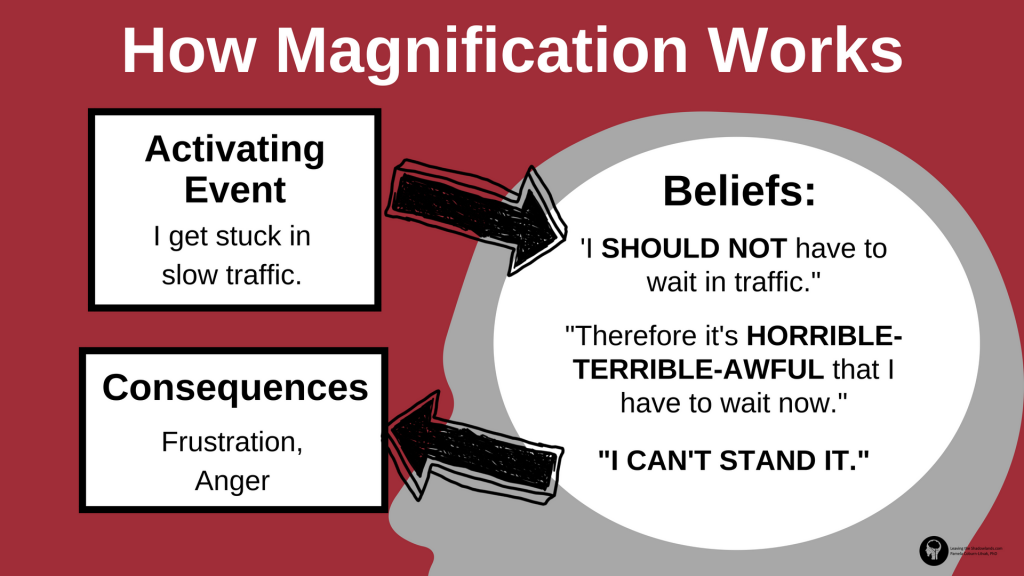

But Matt’s frustration is being fueled even more by a distorted thought pattern called:

Magnification

It’s like using high-powered lenses to view our problems. Suddenly they’re magnified several times their original size, causing us to feel a magnified sense of stress, worry, and conflict.

There’s some common lingo for this distorted thought.

The first is the “horrible-terrible-awfuls.” We make mountains out of molehills, making us feel our problems are so terrible that we just can’t bear it.

So this leads to another common problem called “I-can’t-stand-it-it-is.”

Maybe you and I have thought this way, too.

We make a mistake, and we think, “I can’t stand it when I do something that stupid.”

Or maybe we’re at a restaurant, and someone messes up our order. And we think, “I can’t stand how bad the service is here!”

With magnification, the response is bigger than the problem. Sure, I may get a little frustrated at slow traffic, mistakes, or getting poor service. But are these things really so unbearable that they could finish me off?

Remember the stress scale we used for All-or-Nothing thinking? Magnification basically means we view even small problems at the high end of the scale.

This is also called “catastrophizing,” making problems feel much worse than they are.

Catastrophizers blow their tops when things don’t go their way. Take the problem of slow traffic: catastrophizers tend to be the ones slamming fists on steering wheels, honking their horns, and gesturing to other drivers – and I’m not talking about blowing kisses.

Research shows that catastrophizing is directly linked to higher levels of anger as well as higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety.[1]

On the other hand, those who can downplay or neutralize potentially stressful situations are more resilient to these problems.[2]

Anger Therapy

If you want to learn more about Anger Management, I highly recommend Anger Management for Everyone: Ten Proven Ways to Control Anger and Live a Happier Life.

To whet your appetite, here’s a pinnable version of their principles:

Cognitive therapy can help with the second step of the process: learning how to think about anger triggers differently. It can remove the magnifying lens, helping us see things in a more realistic and manageable way.

The following principles are key to anger management for all of us.

Principle #1: Do Your RESEARCH.

A good place to start is examining the evidence that led to our magnification. We can ask questions like,

- What exactly makes this problem seem so horrible, terrible or awful?

- Is it really so unbearable that we can’t stand it?

- Are we using any other distorted thoughts to prop up our catastrophizing? Are we thinking in “all-or-nothing” terms, exaggerating the facts, using negative mental filters, or jumping to any conclusions?

Principle #2: Be a REALIST.

Next, we want to look at our magnifying thoughts in a more realistic way. Magnification often involves unrealistic expectations. Some of these are our “SHOULDS” – and boy, are these heavy thoughts to carry around. Here are some examples:

- “I SHOULD never get stuck in traffic.”

- “I SHOULD never make a mistake.”

- “Life SHOULD always be fair.”

Sure, we would all love to avoid traffic jams, mistakes, and getting treated in ways we don’t like. But sometimes this stuff happens.

We can get wrapped up in the unfairness of it all, or we can try to re-frame our “SHOULDs” into something more realistic.

How about something like this:

- “It would be nice if I never got stuck in traffic, but it happens. And I can stand it when it does.”

- “I would rather never make mistakes, but I’m human. Mistakes will come. And I can stand it when they do.”

- “I would love it if life was always fair. But I can stand it when the minor things in life are not fair. And I can do my best to make my part of the world as fair as I can.”

Principle #3: Find the Right RATIO.

To find the right cost-benefit ratio, we can ask ourselves,

- What are the costs vs. benefits of believing that life should always be fair?

- What are the costs vs. benefits of believing that I should never make mistakes?

When he’s really frustrated, Matt is tempted to say, “Look, when stuff happens, I have a right to get angry about it!”

And you know what? He’s right.

Matt does have every right to get angry.

But what if he chose not to?

Matt also has the right to live in a way that will remove unnecessary pain and give him the most peace of mind.

To get there, though, he may have to let go of some of his anger.

Principle #4: Follow the Golden RULE.

You may ask, is anger ever the appropriate response?

And the answer is yes, of course.

We’ve all seen people get hurt according to universal standards of fairness. The Golden Rule, treating others the way we want to be treated, is such a standard.

We are responsible for living this way ourselves. And it’s natural to get angry when we or someone else breaks this standard.

But magnification can cause us to equate minor offenses, that really shouldn’t mean anything, with major ones. So we can ask ourselves:[3]

- Are we angry over something major or minor, like a personal preference?

- Was it an honest mistake, where no one intended to hurt anyone else?

For minor stuff, it’s often best to simply let it go and move on.

For major stuff, forgiveness is often the most healing way forward. Forgiveness doesn’t mean we don’t have the right to be angry; only that we are choosing to let go of the wrong.

Lewis Smedes wrote, “To forgive is to set a prisoner free and discover that the prisoner was you.”

[1] Martin, R. C., & Dahlen, E. R. (2005). Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(7), 1249-1260.

[2] Kalisch, R., Müller, M. B., & Tüscher, O. (2015). A conceptual framework for the neurobiological study of resilience. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38.

[3] Burns, D. D. (2009). Feeling good: the new mood therapy. New York: Harper Publishing. 159-165.

Dr. Pamela Coburn-Litvak has published research articles on exercise and stress in Neuroscience and Neurobiology of Learning and Behavior. Her latest book, Leaving the Shadowland of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression, was published in 2020.

After receiving a Ph.D. in Neurobiology and Behavior from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, she served as both Assistant Professor of Physiology & Pharmacology and Special Assistant to the Vice President for Research Affairs at Loma Linda University in Loma Linda, California. She then joined the Biology department at Andrews University and developed courses in human physiology as well as the neurobiology of mental illness. She also founded Rock @ Science LLC, a company that specializes in health and science education and web development. She co-developed the brain and body physiology segment of the Stress: Beyond Coping seminar with its creator, Dr. William “Skip” MacCarty, DMin.

Dr. Coburn-Litvak currently lives in California with her husband. Their two daughters are mostly grown and attending school elsewhere.

When she’s not studying or teaching about stress, she enjoys stress-relieving activities like puttering around the garden, taking nature walks with her family, knitting, cooking, and reading.