Watch the YouTube version of this post!

It’s available here (close-captions and translated subtitles are also available):

Subscribe to my YouTube channel to get access to ALL my videos!

Become a Patron!Some of you may be familiar with my earlier series on cognitive behavioral therapy. I’m re-visiting these concepts as a follow-up to my more recent series on the Four Roads out of Anxiety and Depression.

Hope you enjoy it!

Let’s start with a story.

You can find it in the classic book, Seven Habits of Highly Effective People.[1]

A battleship was assigned to training maneuvers at sea for several days in heavy weather. Visibility was poor, so the captain stayed on bridge to keep watch.

As night fell, a lookout on the bridge called out, ‘Light, bearing on the starboard bow.’

The captain said, “Signal that ship: ‘We are on a collision course, advise you change course 20 degrees.'”

A signal came back, “Advisable for you to change course 20 degrees.”

The captain said, “I’m a captain. You change course 20 degrees.”

“I’m a seaman second class. You had better change course 20 degrees.”

By this time, the captain was furious. He spat out, “Send, ‘I’m a battleship. Change course 20 degrees.'”

Then came the reply that made all the difference:

“I’m a lighthouse.”

There are 2 reasons why I shared that story with you.

I’ll share the second at the end, but here’s the first.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the gold standard for the two most common mood disorders in the world: anxiety and depression. These affect a lot of people – about one in every five adults suffer from one or both every year. [2]

Think of CBT as a lighthouse, warning us of danger points in our emotional landscape and guiding us to safety.

Chances are very high that you – or someone close to you – can benefit from CBT.

Research shows that CBT effectively treats:[3]

- Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Panic Disorder (PD)

- Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD)

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Phobias

- Anger management

- Insomnia

- Hoarding disorder, and even

- Managing job stress

Brain scans show that CBT changes the way the brain works, including parts that regulate our mood and help us make decisions.[4]So, in a very real way, CBT transforms the way we think and feel.

Three Principles of CBT

To help us understand the basic principles behind CBT, let’s think of another, real-life example.

Ted is a college student who took a test this morning. He studied hard and was hoping to get a perfect score. But he didn’t.

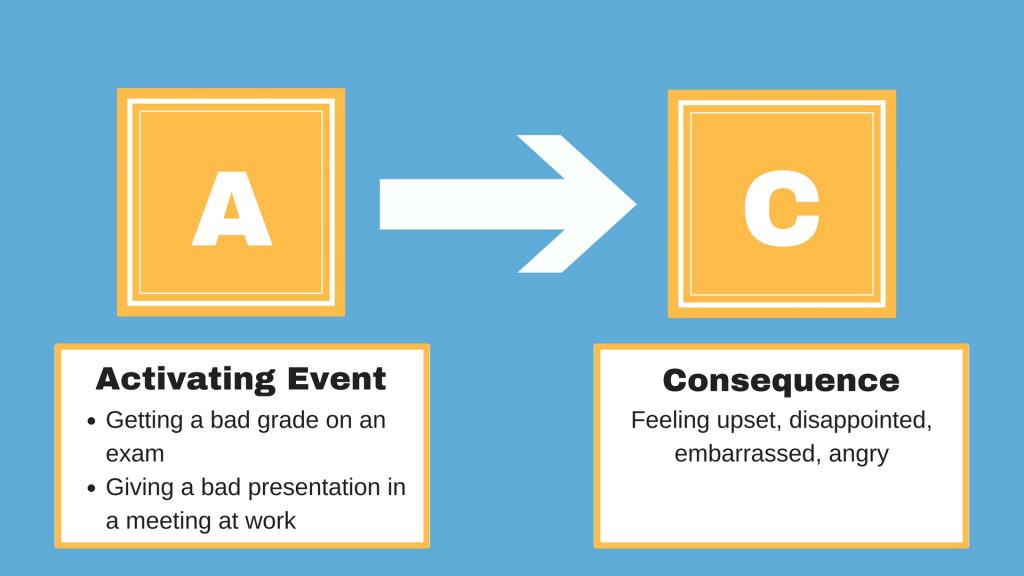

Which is why he’s so glum. We’ll call his test results the “Activating Event,” A for short. We’ll call Ted’s disappointment “C,” the Consequence.

We can all relate, right?

And we often think this is how we get into a bad mood.

When we work really hard at something, we all tend to feel let down when we don’t do as well as we wanted to.

But think about that for a minute – the reason why we get upset is not the event itself, but an unfulfilled expectation or hope that we had for it. Ted wanted to do well, but he didn’t.

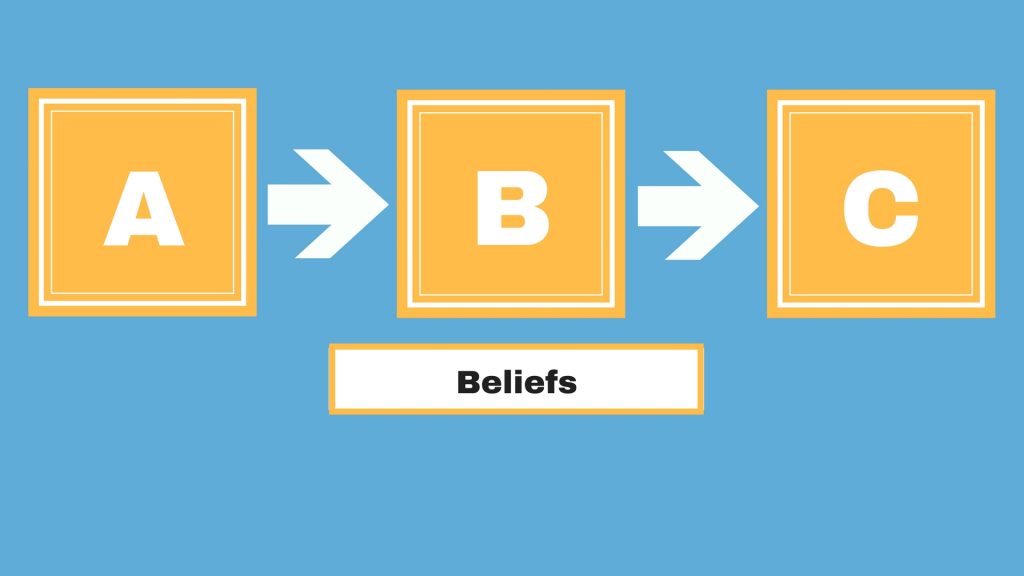

In other words, the Activating event (A) does NOT lead directly to the Consequence (C). There’s something else inserted in the middle.

Principle #1 of Cognitive Therapy

The first principle of CBT is, everything that happens to us is mentally filtered through our Beliefs (B).

We’ve known this first principle for a long time. Over 2000 years, actually. The Greek philosopher Epictetus wrote,

It is not the things that disturb us, but our interpretation of their significance.”

This is also a pervasive concept in contemporary psychology. Psychologist William Lovallo wrote the following:

We may find that a major personal disappointment, say failing to get into graduate school, causes great emotional distress. Or the sound of footsteps on a dark street may provoke a feeling of terror. The disappointment may evoke physical sensations of sadness, lethargy, or even tears of grief. The footsteps may result in fear along with a racing heart and rapid breathing.

The key point to these two examples is that the individual’s physiological responses started out as thoughts and interpretations, mental events that are not in fact physically threatening, and which in a real sense are not things at all. The emotions and physiological responses arose because of his or her interpretation of the event and its perceived meaning in terms of his or her well-being (emphasis mine).”[5]

Note the connection Dr. Lovallo makes here between stress and depression: it’s all about the way we perceive things.

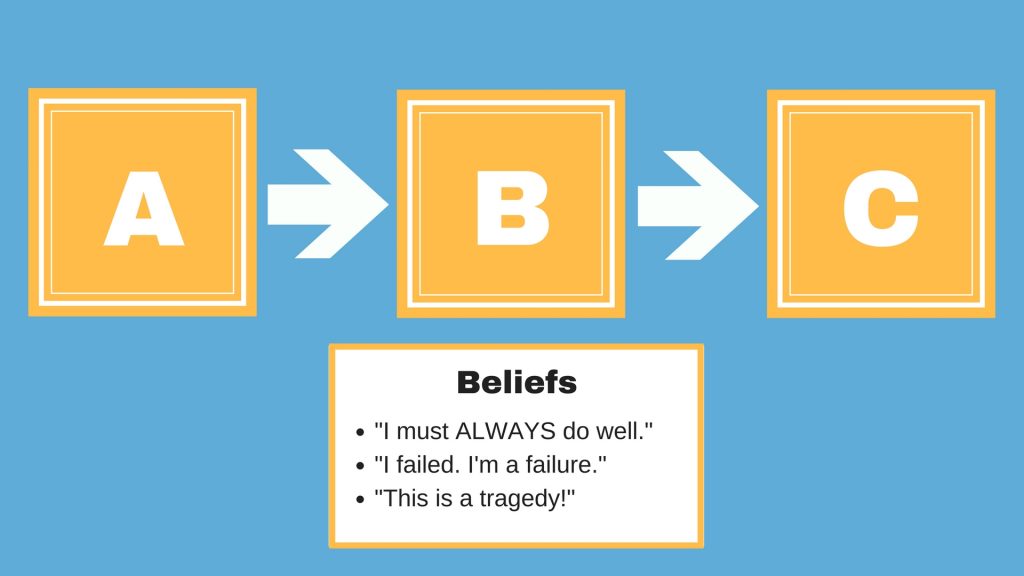

Maybe Ted is thinking:

- “I should always do well on tests.”

- “I’m a failure.”

- “This is a nightmare!”

It’s easy to see how any, or all, of these thoughts would drag Ted down. They’re like rocks in a rough sea, shipwrecking us in dark and bleak waters.

Principle #2 of Cognitive Therapy

Which leads us to the second principle of CBT: Anxious and depressed people spend a lot of time in these waters.

Most of their beliefs skew to the negative, and their feelings follow.

Principle #3 of Cognitive Therapy

But don’t miss the third principle, which is key to the whole thing.

In depression and anxiety, the problem is not with the emotions themselves.

Rather, the problem is almost always the underlying belief that causes the emotion.

These beliefs are almost always distorted to give us a twisted and unrealistic view of the world.

We can all relate to Ted’s disappointment over a poor grade. Chances are, we’ve been there ourselves.

But let’s compare two different sets of thoughts he could have had:

“I got a C on that test. That means I need to learn some new study habits and join a study group. I can find ways to improve on the next one.”

The resulting emotions will include disappointment, sure, but also determination to learn from past mistakes and do better in the future.

Compare that to, “I got a C on that test. That means I’m a complete failure and I will never graduate and I will never get a job and I will never be able to support my family and my spouse and kids will eventually leave me and I will grow old and die alone and miserable.”

These beliefs can easily turn a minor disappointment into a major emotional crisis.

Here’s the key point:

Distorted beliefs are bound to cause distorted emotions.

This is how we skew our world to the negative, making us see danger and disappointment that is not there.

When the belief has been corrected, the emotional response will also be corrected.

Now, for the other reason I told you the story at the beginning.

We often think we’re perfectly justified in our emotional responses to things, just like the captain of that battleship.

But as soon as our beliefs change, our emotional response can change as well.

CBT can guide that process, shining a light on dangerous beliefs and leading us into safer, emotional waters.

So, the next step is to describe the main types of distorted beliefs found in anxiety and depression.[6] That’s what we’ll do in the rest of this series.

And I hope you’ll join me!

Become a Patron![1] Covey, S. R. (1989). The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Simon & Schuster. 33.

[2] Steel, Z., Marnane, C., Iranpour, C., Chey, T., Jackson, J. W., Patel, V., & Silove, D. (2014). The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 476–493.

[3] Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I. A., Karyotaki, E., Reijnders, M., & Huibers, M. J. (2016). How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta‐analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry, 15(3), 245-258.

Springer, K. S., Levy, H. C., & Tolin, D. F. (2018). Remission in CBT for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review.

[4] Rubin-Falcone, H., Weber, J., Kishon, R., Ochsner, K., Delaparte, L., Doré, B., … & Miller, J. M. (2018). Longitudinal effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression on the neural correlates of emotion regulation. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 271, 82-90.

[5] Lovallo, W. R. (2015). Stress and Health: Biological and Psychological Interactions. Sage publications. 33-34.

[6] Burns, D. D. (2009). Feeling good: the new mood therapy. New York: Harper Publishing. 9-13.

Dr. Pamela Coburn-Litvak has published research articles on exercise and stress in Neuroscience and Neurobiology of Learning and Behavior. Her latest book, Leaving the Shadowland of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression, was published in 2020.

After receiving a Ph.D. in Neurobiology and Behavior from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, she served as both Assistant Professor of Physiology & Pharmacology and Special Assistant to the Vice President for Research Affairs at Loma Linda University in Loma Linda, California. She then joined the Biology department at Andrews University and developed courses in human physiology as well as the neurobiology of mental illness. She also founded Rock @ Science LLC, a company that specializes in health and science education and web development. She co-developed the brain and body physiology segment of the Stress: Beyond Coping seminar with its creator, Dr. William “Skip” MacCarty, DMin.

Dr. Coburn-Litvak currently lives in California with her husband. Their two daughters are mostly grown and attending school elsewhere.

When she’s not studying or teaching about stress, she enjoys stress-relieving activities like puttering around the garden, taking nature walks with her family, knitting, cooking, and reading.

[…] to part 2 of my series on cognitive therapy, the gold standard for dealing with depression and […]

[…] part 3 of my series on Cognitive Therapy, let’s meet […]

[…] In part 4 of my updated series on Cognitive Therapy, […]

[…] what Part 5 of my series on Cognitive Therapy is all […]

[…] part 6 of my series on Cognitive Therapy, let’s meet […]

[…] part 7 of my series on Cognitive Therapy, let’s meet […]

[…] part 8 of my series on Cognitive Therapy, let’s meet […]

[…] part 9 of my series on Cognitive Therapy, let’s meet Nick. Nick’s a brand-new college grad and started a new job last […]

[…] part 10 of my series on Cognitive Therapy, let’s meet […]

[…] This is the last installment for my series on Cognitive Therapy. […]